Louis Braille

At just 15 years old, he took a clunky military communication system and turned it into a sleek, dot-based code so brilliant it made the alphabet jealous. While most teenagers were busy figuring out how to sneak into a workplace, Louis was busy sneaking accessibility into the world.

#about

When life said, "No reading for you," Louis responded, "Not this time."

#lessons

The best inventions aren’t about fame or fortune

– they’re about helping people.

#quotes

"We do not need pity, nor do we need to be reminded we are vulnerable. We must be treated as equals – and communication is the way this can be brought about."

Internet, microwave ovens, superglue, disposable menstrual pads, Braille system... What do they have so much in common that it allows to have all in one line? To a lesser or greater extent, all these inventions have their roots in military service.

What? You’ve never heard Braille having been a soldier? Sure. He never was one. But he was a very attentive student whose best wish was to be able to read, write, and communicate with the world when being blind.

Curiosity killed the cat…

Louis lost his sight as a kid, a very curious kid who wanted to know badly how various instruments and tools used by his father worked. The instruments were long and sharp, and the 3-year-old toddler was too quick when trying to play with them. That’s what resulted in Louis’s complete blindness by the age of five.

…but satisfaction brought it back.

It was probably the only time when Louis would establish contact with a military worker, although retired.

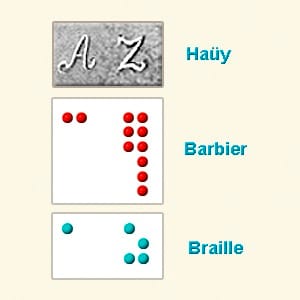

His name was Charles Barbier. Serving in the French artillery, the man became interested in alternative writing forms like shorthand writing, phonetic scripts, codes for secret communication, and even sending messages without using a pen. He studied systems used in different circumstances by different groups of people (e.g., by soldiers for night writing, by deaf or blind people in everyday life, etc.), and came up with his own innovations. Barbier did not mean them specifically for military service, but he did encourage such application, too. His main aim was to make both reading and writing easier for poor people and those having impaired hearing or vision.

Barbier’s first attempts to contact the Royal Institution for Blind Youth were either directly rejected or silently ignored for personal interests and fears of the school directors. But when after two years he managed to reach the students with a specifically developed system of 12 embossed dots instead of regular letters, they certainly enjoyed the innovation.

Louis Braille was the first one to start speaking about the disadvantages: 12 dots took more space than a fingertip could cover, so the process of reading would slow down; there were no numbers and no punctuation marks. Several years later, in 1729, Braille presented his own system of 6 embossed dots based on that once created by Barbier. That’s the script in use today, which has also been adapted for mathematics and musical writing.

Barbier discovered the system four years after it had been published and became ...absolutely happy. Even though he had no initial idea who Braille was, his friendly letter included congratulations and apologies for not using Braille’s system yet.